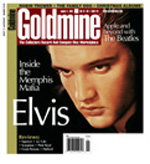

Elvis graces the cover of the upcoming issue of the US record collector magazine, Goldmine. This edition features an interview entitled "Discover the real Elvis, according to Memphis Mafia insider Jerry Schilling" by Ken Sharp ("Writing for the King") most of which will be familiar to those who have read his recent book.An excerpt:

Back in 1954, the mighty hand of fate struck down hard on a gangly, 12-year-old, North Memphis youth named Jerry Schilling. It was there on a local football field that he first met a wild hillbilly cat known as Elvis Presley.

The two forged a close friendship that lasted from the mid-’50s until Presley’s death in 1977. Schilling was a trusted friend and confidante who enjoyed an eyewitness take on life inside the gates of Graceland.

The last holdout of “The Memphis Mafia” to pen a book about his friend, Schilling has written “Me and A Guy Named Elvis” in collaboration with writer Chuck Crisafulli. It is a frank, warm and candid memoir of his life with “The King of Rock and Roll.”

And despite his continued closeness with the Presley family (Jerry was Lisa Marie’s first manager and he maintains a strong friendship with Priscilla), the book is not a whitewash. Instead, it offers a strongly balanced, keenly insightful and, most crucially, human portrait of the music superstar. Like an onion, Schilling skillfully peels back layer after layer of the myth, and in the process reveals the real Elvis, an immensely talented man with flaws, doubts and insecurities like the rest of us. And in humanizing Elvis, it makes him that much more real, relatable and likeable.

What made Schilling stand out from Elvis’ coterie of buddies was his desire be his own man and forge a career away from Graceland. In between stints working for Elvis, he managed the likes of The Beach Boys and Jerry Lee Lewis, honed his editing chops working behind the scenes on such projects as the acclaimed 1972 documentary “Elvis On Tour” and lent his expertise to such television projects as biographies on Brian Wilson and Sun Records chief Sam Phillips and the multi-hour documentary “The History Of Rock & Roll.”

Packed with colorful stories about life inside the recording studio, on film sets, on tour and Elvis’ meetings with the likes of The Beatles, Richard Nixon, Brian Wilson, Led Zeppelin and others, “Me And A Guy Named Elvis” is an indispensable primer illuminating the legacy of the most influential musical icon of the past century.

Goldmine: Why did you hold out so long to do a book?

Jerry Schilling: There was a long period of time after Elvis passed away; professionally or publicly, I didn’t talk about Elvis. I tried to go on with my life professionally. There was no way I could ever make up for the loss of Elvis personally.

I had a management company, and I was managing The Beach Boys and Jerry Lee Lewis and worked with Billy Joel. I was more fortunate than some of my friends that didn’t have those alternatives. I never expected to lose Elvis, especially at that young age. After about 10 years, I went to work for Elvis Presley Enterprises as creative affairs director. I also got to work as a producer, and I produced about nine documentaries on Elvis, shows like “Elvis: The Great Performances.”

GM: What does your book tell us about Elvis that others have been unable to convey?

JS: I had gone back to Memphis. They had done a nationwide search to find a president and CEO of The Memphis Music Commission, and I got the job, which was unbelievable. I did that for a little over three years.

After my term was up, I came back to L.A. My wife got very sick for a short period of time. I stayed here with her, and we were talking about our lives. I thought maybe I could write something on my life with Elvis. But I thought, “There’s been so much written on Elvis; could I do something that was not overdone?” As I would tell my wife stories, I felt there was a reason to do a book.

I had become very close friends with Peter Guralnick when he was doing his books on Elvis (“Last Train To Memphis” and “Careless Love”). If I was gonna do it, I wanted to do on a first-class basis and honor my friend. Peter kind of guided me a little bit.

I spent six months doing a proposal with my co-writer, Chuck Crisafulli. We put together chapter four, which was about when I went to work for Elvis and the bus drive from Memphis to L.A. I was pleased with it. I felt that Chuck got my voice. What was really important to me was not to write a book about my life with Elvis as who I am today or what’s happened in the last three decades. I wanted to go back to who I was then, a shy guy who was happy to be with Elvis. I really wanted to do this book as a piece of history.

Also, there’s this iconic view of Elvis, and that’s wonderful, but I thought a big thing was missing here, which was the human side of it. I really felt I knew that side, and I was very fortunate to experience it. I realized about three years ago that I had a book that would be a good historical record of Elvis as a human being.

GM: You first heard Elvis’ music on WHBQ’s “Red, Hot & Blue” radio show.

JS: I had been listening to Dewey Phillips on the radio since I was 10 years old. Before Dewey came onto the scene, I was hearing what my parents listened to, the hit parade. It was good, but it didn’t connect with me.

But, around that time, there was a group of white kids who were starting to listen to the rhythm and blues that Dewey Phillips was playing. He’d play everything — R&B, Dean Martin, Little Richard, The Platters. All that stuff was a big influence on Elvis, too.

When you think of how diverse Elvis was, I mean, look at the first album. You’ve got country, rhythm and blues, rockabilly ... everything. But, rock and roll was the music that was dangerous.

We can never forget that rock and roll was born out of segregation. It was dangerous for us to go down to Beale Street to buy our records. Our parents would have grounded us forever if they found out. It was a totally segregated society. Beale Street was black. Main Street was white. In the middle of all of that, Dewey Phillips played a record called “That’s All Right Mama” by a boy from Humes High School. He had to say Humes High School, because the audience would then know that he was white. Dewey played predominately black music. When “That’s All Right Mama” came on the radio, it was so exciting. It rolled it into something to be a part of.

GM: Take us back to how you came to meet Elvis.

JS: The first time I heard Elvis was in the second week of July 1954. That Sunday, July 11, 1954, I go over to my local playground in North Memphis — a very poor neighborhood. There were five older boys in and out of high school trying to get up a football game. That’s how unpopular Elvis Presley was at that point. Elvis was just starting out, and nobody knew who he was yet.

Red West, a friend of my older brother’s, knew I played grade school football. He said, “Jerry, do you want to play with us?” Little kids love to play with the big guys, so, of course, I said, “Sure.” We get in the huddle, and I swear to God I saw the other guy and said, “That’s the boy from Hume High that sang that song I just heard on the radio.” His name was never mentioned.

Why I knew that, I don’t know. He didn’t look that different. He looked cool. His hair was a little bit longer than the other guys, and he was damn good looking. He reminded me of characters I’d seen in “Blackboard Jungle.” He was like one of those guys that I wanted to look like in “Rebel Without A Cause” or “The Wild Ones” with (Marlon) Brando. Elvis was not the guy you walked up to and slapped him on the back, and you became friends because you pl

Elvis In Goldmine Magazine

January 04, 2008 | Other