It was a quiet Sunday 60 years ago when the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor. This Sunday, 40 years ago, Pearl Harbor was anything but quiet. The King was in the house.

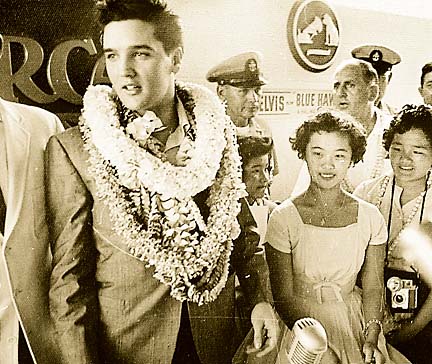

On March 25, 1961, Elvis Presley made his first post-Army appearance, and he did it for the Navy. Presley performed in a charity fund-raiser at Bloch Arena to kick-start the struggling USS Arizona Memorial building fund.

It is an event largely unremembered and unmemorialized, even though a rock 'n' roll entertainer was able to accomplish something that admirals, generals and politicians could not.

More than a thousand U.S. sailors were entombed in the battleship when a bomb ripped apart the bow, splitting the hull. It sank in minutes and the bodies were never recovered.

Dozens of plans were proposed to memorialize the crew of the Arizona, the U.S. Navy's single greatest loss of life, but for nearly 20 years military efforts at raising funds were fumbling and disorganized. There was also no agreement on the size and shape of the memorial.

Eventually, a design by architect Alfred Preis was accepted, even though the Navy had asked for a memorial shaped like a ship's "bridge" and Preis' design was like a bridge crossing a river.

Although the U.S. Navy insisted on complete control of the Arizona Memorial, they had no experience in creating such structures. The Navy's fund-raising was confused, and ineffective, even when they hired civilians to do it for them.

Hawaii journalists appealed to other newspapers to help. George Chaplin of the Honolulu Advertiser mailed something like 1,500 letters, asking for articles or editorials about the Arizona Memorial. The Los Angeles Examiner responded with an editorial, and one of their readers that day was Elvis Presley's manager, Col. Tom Parker.

"The colonel read in an L.A. newspaper that the memorial-building project was not going to be finished," recalled radio personality and concert promoter "Uncle Tom" Moffatt, a friend of Parker's.

According to Ron Jacobs, another KPOI "Poi-Boy" disc jockey at the time, "Parker, a veteran of World War I, served in the U. S. Army at Fort DeRussy in Waikiki and loved Hawaii.

"Elvis did his first concerts here in November 1957 at the Honolulu Stadium. That is when Tom Moffatt and I met Elvis and Col. Parker. We were disc jockeys and the first ones to play Elvis' records. Colonel invited us to emcee one concert each. That remains one of the most exciting experiences of my life."

The benefit was also an opportunity for Presley to ease back into playing for a live audience. Presley was just getting out of the Army and he hadn't performed for a couple of years. Presley also wanted to do something patriotic for his country after serving in the military.

"Chaplin was a veteran of World War II who served on the staff of The Stars and Stripes, the official U. S. military paper," said Jacobs. "Several other Stars staff members were discharged in Honolulu and joined Chaplin."

USS Arizona Memorial historian Dan Martinez credits newspapers for keeping the memorial concept alive. "Editors of daily newspapers across the country were connected in their profession, that was how they kept the story going.

"Parker and Elvis had to go to Hawaii anyway, to film a movie they thought would be called 'Waikiki Beachboy' (it turned out to be "Blue Hawaii"), so Parker thought it would be good publicity to schedule the benefit concert that would raise well over $64,000 for the memorial.

"But the memorial needed half a million dollars. The total already raised at that time was $250,000, which was only half of what they needed. Federal money was eventually taken to finish the memorial, which means that half the money that was raised later came from the taxpayers," said Martinez.

But before the concert could go on, Parker had to convince "the brass," admirals, generals, etc., that a benefit concert would actually be profitable. The military officers were skeptical, said Moffatt.

Moffatt went with Col. Parker to "see the reaction" of the officers. "It was still the early days of rock 'n' roll, which conservative people still thought of as wild music. But Col. Parker was such a great salesman that by the end of the meeting, the colonel had the brass saluting him," Moffatt recalled.

Jacobs also remembers the summit meeting. "Moffatt and I were on hand when Parker briefed the highest military in the Pacific. Although he was an 'Honorary Colonel' from the state of Tennessee he had the authentic generals and admirals hypnotized when he spoke. As the officers left, they were each given a photo of Elvis. They had to restrain themselves from looking like excited fans."

"Our sincere thanks to Col. Parker," said Pacific War Memorial fund-raising chief H. Tucker Gratz afterward to the press. "It's hard to believe this is real."

"It is," said Parker. "You know, Elvis is 26. This last Sunday was his birthday and that's about the average age of those boys entombed in the Arizona. I think it's appropriate that he should be doing this."

Star-Bulletin columnist Dave Donnelly was a news editor at KPOI when he happened onto the interview among Moffatt, Jacobs and Parker announcing the concert. "Col. Parker waved his hands at all these kids who were sitting in the studio and said, 'You're all invited too,' and they were. He bought their tickets," Donnelly said.

The concert was scheduled for Mar. 25, 1961, in the Bloch Arena next to the Pearl Harbor entrance. The goal of $50,000 was topped by almost $15,000. Tickets were sold at stores like Sears, for a top price of $5.

The concert not only raised money, it also raised public awareness of the need for a memorial. All funds raised went into planning and building the Arizona Memorial; Elvis wasn't paid his usual fee of $25,000.

"I don't believe in part-time charities," said Col. Parker. "Elvis will not receive a cent for his evening's work."

"Parker believed that if you did a fund-raising concert that all the money made, every penny of it, went to the cause," Moffatt explained.

Even Elvis purchased tickets. Col. Parker and the admirals bought tickets to the show to increase the total amount raised. "The colonel made sure that absolutely no one got in the show for free," Moffatt said.

Many $100 tickets were sold, and Presley bought the first one.

The show was memorable. "Because it was a small indoor hall, the screaming and cheering was louder than the 1957 outdoor shows. It was literally a situation where you couldn't hear yourself think," Jacobs said.

"On the night of the show there was the electricity and excitement that was felt only at Elvis concerts. I have attended many concerts. The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Michael Jackson, 'N Synch, etc., never generated the highly charged audience reaction that Elvis did.

"I was amazed at how much music such a small group of performers could generate. Elvis' onstage moves, which have since been widely copied, captured visually what his music sounded like. To me, the most exciting moment was when Elvis ended his smash-hit song 'Hound Dog' by landing on both his knees and skidding at least 6 feet across the stage.

"Minnie Pearl, a comedy 'hillbilly' singer and star of 'The Grand Ol' Opry' radio and TV show received 'special guest' billing. Parker brought Elvis' complete road show and touring band. They were most of the original musicians and singers on Elvis' first records: D.J. Fontana on drums, Scotty Moore on guitar and the Jordanaires as backup singers."

There had never before been a high-profile fund-raising concert -- especially not one by a rock 'n' roll performer. Despite this contribution, there is no mention of Presley's special concert at the Arizona memorial itself or at the visitors' center.

There is only one plaque at the memorial that mentions Presley as just one of the many contributors

Elvis Shook It Up 40 Years Ago For The Arizona Memorial

By Burl Burllingame, March 25, 2001 | Other