Greil Marcus is a rock-critic legend. A graduate of the late-'60s Berkeley scene, Marcus began his rock and social criticism with then fledgling Rolling Stone magazine and quickly became notable for his highbrow style and brainy approach. His obvious talent and his professorial passion for dissecting rock and roll had an air of academic credibility, brought a new seriousness to the critical art form, and moreover displayed a keen foresight for the more widespread effect that rock music was having on mainstream American pop culture. Over the course of a half-dozen or so books, countless magazine articles, various liner notes, and a few new media (Internet) news outlets, Marcus has touched upon nearly every facet of 20th-century popular music and culture, but none more so than Bob Dylan and Elvis Presley (what seems like nearly half of Marcus' collective output brushes up against these two American icons).

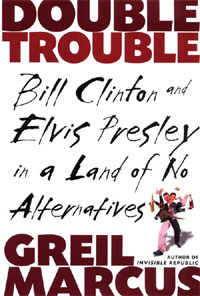

With Double Trouble: Bill Clinton and Elvis Presley in a Land of No Alternatives, Marcus returns to the familiar subjects of the King and Dylan. Unfortunately, the subject matter now feels more tired and opportunistic than relevant. Double Trouble is a linear collection of Marcus' articles and essays from the eight years that span the course of Bill Clinton's 1992 campaign and subsequent presidency. In an effort to bond the varied pieces into a cohesive unit (or simply to take advantage of Elvis as a selling point), Marcus takes an enormous, straight-faced leap of faith that borders on self-parody when he tries to link Presley and Clinton directly. It's an interesting concept--one that at least shows effort in connecting this anthology--but when Marcus remarks, "The idea of Clinton's presidency as an Elvis movie is almost irresistible," as he does in the book's introduction, you get the feeling you're about to be cheated. (Marcus' chosen title, Double Trouble, even graced one of the King's motion picture efforts.)

Sadly, however, Marcus finds his Presley-Clinton linkage in coincidental absurdities. "Nine days ago, on January 8, 1993, the Postal Service issued the Elvis stamp; three days from now Bill Clinton will be inaugurated as the forty-second president of the United States. This confluence of circumstances is not exactly an accident"--a fairly ridiculous notion, which Marcus proceeds to weigh via his usual skillful but gymnastic wordplay. Leaping from ambitious assertions straight to a roundabout consideration of the numerous playful Elvis references during the 1992 Clinton campaign, such as Clinton's heady saxophone-playing appearance on The Arsenio Hall Show (a sunglasses-wearing Clinton tooted out an amateurish "Heartbreak Hotel"), Marcus never lays down sincere evidence behind his "not exactly an accident" statement --unless, of course, Marcus now believes that metaphor equals truth.

Marcus is far more on his game in Double Trouble when he critiques the current culture and attempts to take stock of things as they stand. The pieces of this collection that bloom when Marcus walks away from the comfort of Presley display that his writerly intuition still tends to serve him very well.

The book replays an essay from Rolling Stone about Kurt Cobain ("A Look Back"), which the magazine used as the basis for its "Artist of the Decade" issue in 1999. The story seems to reflect a slight but not passing disdain for and disconnection from the movement of modern-rock culture. He starts to show his age, and the piece gives us Marcus at his semi-hypocritical best. As he waxes poetic in the realm of "maybes"--once again never committing himself to the deed to be done--Marcus quickly loses any scent of credibility to the "Artist of the Decade" argument with looping, unconvincing statements such as "If Cobain, speaking through Nirvana, had done nothing but write and record 'Smells Like Teen Spirit' and make it a hit, he might still be a step ahead." He hedges his bets at the end of the piece, saying, "Kurt didn't offer any solutions, he just railed against the ugliness and made it his home...He wasn't brilliant or even all that articulate, but I liked to scream along." Marcus remains elusive and noncommittal while writing as poetically as ever.

Late in Double Trouble, Marcus hits upon a thought that might ultimately be the best assessment of his talents by anyone. He recounts a story about a literary forum in which he shared the stage with music writer and prolific Presley biographer Peter Guralnick, who told the audience, "My approach to writing is the same as my approach to coaching baseball. I tell the kids, 'Don't speculate. Stay inside the game.'" Marcus seizes the moment to respond: "My approach is the opposite--speculate; get outside the game--and I think that to find a person who so completely entered the souls of others as Elvis Presley did, you have to do that."

Marcus always has worked outside of the lines; it's what keeps him arresting if not always essential. Yet he still works within a clear set of parameters (perhaps not "outside the game," but playing a different game altogether--with different lines), clinging to Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan like a child clutching a favorite, familiar blanket.

In Double Trouble, Marcus begins to reek of an old man whose generation has come of age. It's no surprise that Marcus identifies with and leans on characters such as Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, and now President Clinton. They're all--Marcus included--of the first rock-and-roll generation: an intelligent and undeniably talented one filled with passion, ideas, and the utmost potential. But they're also of a generation best embodied by a president who struggles, when put up to the light, with something as simple as defining the word "is."

Double Trouble: Bill Clinton and Elvis Presley In A Land Of No Alternatives

By Kurt Henron of the Dallas Observer, October 13, 2000 | Book